Seventy years ago Nook Farm was destroyed by German bomb. This is vividly recalled by George Moss in his book “Village of Moonbeams” first published by CC Publishing in 1998 and reprinted in 2008.

To commemorate this CC Publishing have kindly allowed us to reproduce this extract.

“Village of Moonbeams” can be purchased from CC Publishing on their website at http://www.cc-publishing.co.uk/ and used copies can be found on the usual internet outlets.

Extract from Chapter 4 – A Village At War

The war progressed quietly and peacefully enough for us in the village until my own life was to be devastated. My most horrific memory of the Second World War takes me back over half a century to November 28th, 1940, when I was just I4-years-old and living at Nook Farm with my grandparents, George and Edith Moss.

I had lived at Nook Farm with my grandparents for most of my early life, having gone to live there when my sister Eileen was born, to ease the burden for my mother, and, as happened very often in Cheshire farms, my grandmother was loath to let me return home. Therefore, I remained while my sisters, Eileen and Doris, and my brother, Ken, were brought up first in Nook Cottage and then at Hefferston Grange Farm, and so although I visited my mother and father regularly, I was at Nook Farm with my grandparents that fateful night.

Nook Farm, with its lovely old ivy-clad farmhouse, stood at the junction of West Road with Grange Lane, which came to be known as “Moss’s Comer.” The farm was thought by many to have the prettiest farmhouse and buildings in the village, with its lovely garden and apple and pear orchard, especially at blossom time in the spring. It was just over a year since the outbreak of the war and already there had been about 40 air raids on Merseyside. Apart from the anti-aircraft guns, there seemed to be no other opposition as, during the long summer evenings just past, it was possible to follow the air raids on Runcorn, by watching the little balls of black smoke with their red centres from the exploding anti-aircraft shells.

This day, Thursday, 28th November, had been dismal, becoming quite foggy by early evening. In the nearby wood, owls were hooting ominously as if they had a premonition of what the night had in store.

Before 8 o’clock the fog seemed to be clearing a little, and searchlights began sweeping across the night sky. Soon afterwards we could hear distant gunfire and it was not long before the familiar drone of German aircraft could be heard, although no warning sirens had sounded. It was not until some time afterwards that we learned that due to the widespread fog across the country, the bombers had flown around the coast to attack Liverpool from the Irish Sea, thus taking the early warning system by surprise.

It was soon evident, by the number of aircraft overhead and the intense barrage of anti-aircraft fire, that this raid was going to be heavier than anything we had experienced before. The dull thud of bombs exploding not too far away was becoming alarming and frightening. My grandfather had retired to bed early, to prepare for an early start on the milking the next morning, and we had decided to stay by the warm kitchen fire, rather than go to the cold air-raid shelter, as we had done on most previous occasions. This air-raid shelter we had built in the orchard, well away from the house and farm buildings, but because of the cold, and I also had my homework to do, we stayed in the kitchen with the farm fire burning in the grate.

The noise was increasing, almost beyond endurance, and when an old cat, which had been sharing the hearth with us, went to the door to be let out, I seized the opportunity to have a look outside.

I followed the cat across the cobbled farmyard as she ran through a passageway between the buildings and scampered off across the fields. We never saw her again. Over towards Overton Hills, the orange glow of fires in Liverpool could be clearly seen, and clusters of flares suspended by parachutes hung like huge chandeliers in the sky, lighting up everywhere like day. It was a very frightening sight.

Suddenly, a large 500lbs, bomb exploded a few fields away and the blast shattered the glass in a garden frame leaning against the farmhouse. Then, as if sown by some giant hand, shoals of incendiary bombs exploded with a brilliant blue flash along the fields, at the side of the railway, which must by now have been clearly visible to the bombers above. I was worried about the danger by fire to the two large haystacks standing in the stackyard. I ran back into the house and as I got inside my grandfather was coming downstairs to join us. Once again, we settled down around the hearth. Then, suddenly, there was a blinding flash of light, a mighty rumble, and the old house shook and disintegrated around us.

Only the huge oak beams saved us from being crushed to death as the house fell upon us, filling the air with dust and the acrid fumes of the soot from the chimney; soot which we were to taste for weeks because of the amount we must have swallowed. I remember hearing no clear explosion, just a prolonged deep roar. I was hurled from my chair and ended up under a pile of debris. My grandfather remained calm and took charge of the situation. Although he was deeply shocked, he had no actual injuries. Unfortunately, I had been in a position with only the window between myself and the terrible blast and, consequently, I was dreadfully injured by the flying glass.

There were six of us in the farmhouse at the time, my grandparents, two aunts, an uncle, and myself, and also a little fox terrier Pip who had been so frightened by the noise of the earlier part of the raid that he had been almost hysterical. My uncle, who had been sitting next to me, suffered severe head and face injuries on his right side, while I received serious injuries to my spine, head, face, left eye and left arm. I could not speak to tell anyone where I was, but after a careful search in the darkness, my grandfather found me, removed the rubble from around me, took me outside, and laid me down in the rubble-strewn garden. It was some time before I found my voice; my left arm would not move, and with my right hand I felt the terrible damage to the left side of my face. I found myself blind in my left eye and with very little vision in my right, and I could feel the blood running down my back.

There were six of us in the farmhouse at the time, my grandparents, two aunts, an uncle, and myself, and also a little fox terrier Pip who had been so frightened by the noise of the earlier part of the raid that he had been almost hysterical. My uncle, who had been sitting next to me, suffered severe head and face injuries on his right side, while I received serious injuries to my spine, head, face, left eye and left arm. I could not speak to tell anyone where I was, but after a careful search in the darkness, my grandfather found me, removed the rubble from around me, took me outside, and laid me down in the rubble-strewn garden. It was some time before I found my voice; my left arm would not move, and with my right hand I felt the terrible damage to the left side of my face. I found myself blind in my left eye and with very little vision in my right, and I could feel the blood running down my back.

Not knowing the extent of my injuries, my grandfather had laid me down on some coats he had brought from the wreckage and covered me with others. My grandmother, even though she was in a very bad state of shock, and with cuts to her face and arms and a nasty eye injury, prayed that we might all see daylight.

Still the planes droned overhead. There was no let-up in the gunfire and the shrapnel was falling like hail. Cyril Catley, the village chemist, and Chief Air Raid Warden, happened to be patrolling on foot in West Road, and although he was blown off his feet and through the hedge at Tilston Hayes, the home of Mrs Bruton, he managed to get to that house and telephone for help.

He had no trouble getting into the house to telephone as the front door had been blown off its hinges. It seemed like ages as we waited in the intense cold, bleeding profusely from our injuries, for help to arrive. Soon more wardens arrived, followed by a couple of cars, converted into makeshift ambulances, to take us to the stables at Ivy House, Dr. Shaw’s house, where there was a First Aid Post with some St. John Ambulance men on duty. They were local villagers, among them Walter Glenister, Geoff` Burgess, and Jack Nagle, who had manned the Post since its foundation at the beginning of the war. However, my grandmother and I had serious eye injuries and were taken to Hartford Hill in Darwin Street, where a doctor was in attendance. We ended up, after a nightmare ride through the air raid, back at Hefferston Grange Red Cross Hospital.

I do not remember much of the journeys between the First Aid Posts and then eventually to the newly-built Red Cross Hospital, but I do remember the feeling of relief to be back in a warm building where we could be attended to by the wonderful nursing staff which included many local Red Cross volunteer nurses.

Meanwhile, back at the farm, villagers were risking their own lives releasing the cattle that had been trapped in the farm buildings. The shippons by now had no roof and Cattle Warden, Arthur Dean, a local farmer, assisted by other villagers, released those cattle which were in distress and made the others as comfortable as possible until morning came. Although all the cattle survived, they were badly affected by the experience. A collie dog and a pet rabbit survived in a building next to the house.

I was told later that a parachute mine had dropped in the gateway to the farmyard, about 20 yards from the house, where it exploded immediately on contact with the ground. These parachute mines, or land mines, as they were also called, were a comparatively new weapon, designed to cause maximum blast damage and to break morale. They consisted of an aluminium container containing 1,000 lbs. of high explosive, suspended from a 27-feet diameter parachute, of artificial silk.

Windows were broken over a wide area of the village and nearby houses damaged. The gate hinges from the farmyard gate were blown nearly half a mile to the Gate Inn, and even today, fragments of the aluminium container can be found in the fields, hundreds of yards from the spot where the explosion took place.

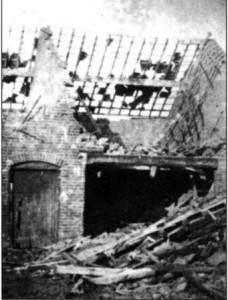

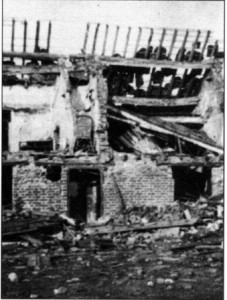

Photographs of the damage were taken the next day by Emie Lamb, who worked at the farm. I am lucky to have these photographs because at that time it was an offence to take photographs of bomb damaged buildings for fear of giving comfort to the enemy, should they fall into their hands.

Ernie gave me the photographs after the war and told me had also had a very narrow escape during the raid. He had been sitting on the roadside seat, opposite the farm, and as the ferocity of the blitz increased he decided to walk his girlfriend home, to Hefferston Grange, where she lived. It was extremely foolhardy to be out as shrapnel from exploding anti-aircraft shells was falling like hail, and it could kill. He then hurried back past the farm to Mary Brown’s chip shop, at the bottom of Forest Street. The shop was a popular eating place and it was business as usual, air raid or not.

As Ernie arrived, an enormous explosion shook the shop and broke windows everywhere. Fear gripped the whole village as people realised something dreadful had happened. The seat on which Ernie and his girlfriend had been sitting was twisted and broken beyond recognition and had been blown over the hedge. The next morning, young Bill Walsh, arriving for work at Nook Farm, was met at the crossroads by the village bobby, Constable Savage, and was told the terrible news. As dawn came, he was shocked to see the devastation caused by the blast. Telephone lines were down, water mains were broken, and there was a crater filled with water. As the War progressed it was not long before Billy Walsh (who sadly has recently died) joined the RAF, and he was to go on many bombing raids over Germany as an air gunner in Wellington Bombers.

After extensive surgery, followed by skilled and dedicated nursing at the Emergency Hospital, I was restored to a reasonable level of fitness, even though I was never ever again to be 100% fit, nor was my eyesight ever to be as good as it should have been.

I was in hospital for weeks and lost a lot of time of school, which I had to make up for by staying on for an extra year. In the weeks of convalescing, I learned to play the accordion and the piano accordion, all of which was to give me a great deal of pleasure in years to come, as well as a second career as a professional musician.

Copyright © 2007 CC Publishing & Roger Moss.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced transmitted or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from CC Publishing.

ISBN 978 O 949001 36 8

CC PUBLISHING, MARTINS LANE, HARGRAVE, CHESTER, CH3 7RX

TEL: 01829 741651. EMAIL: editor@cc-publishing.co.uk

WEBSITE: http://www.cc-publishing.co.uk