Arthur Lambert was just 21 when he was called up in July 1939. After training he joined one of the “crack” units of the Royal Horse Artillery, the Fifth Regiment and in early April 1940 he went to France.

A few weeks passed, the battery were moved around but saw little action and received even less information. What follows are Arthur’s own words.

“Then one day in fields as we went along we saw hundreds of British Army vehicles of all sorts parked close together and set ablaze. We knew then that things had gone wrong and the situation was serious.

Later we were told of the evacuation from Dunkirk. The first party was to leave at about 4am and I was told to be on it. The remainder were to stay behind to do rear-guard action firing.

I got very little sleep and was ready assembled on the road in good time. I had very little kit, as the Quad with my big pack in had got stuck, and was either burnt or vandalised so I travelled light, even my rifle was in that vehicle.

Under one of our officers about 150 men set off in an orderly marching column. We kept going until about 7 am, when we stopped to rest and eat the sandwiches we had been given. The road got more and more congested as we had gone along. The roadside and in places canals were strewn with weapons, vehicles and kit of all sorts. When we set off again it was obvious we were not going to be able to keep an orderly column, as there were now thousands of other troops on the road of all description, so we were told to keep together as best we could. I palled up with 3 others to make a group of 4 men.

We found that a railway ran nearby; no trains of course, but we found that the labour of walking was easier if you stepped from sleeper to sleeper, as one had seen railwaymen do. I got along quite well like this, the only problem was that you had to keep your head and eyes down on where you were walking or you tripped over a sleeper if you missed stepping on it.

We followed the railway towards Dunkirk for some time and then we came to the suburbs of Dunkirk. We made our way towards the sea but we had to take cover in a deserted café, as an enemy aeroplane or more came over, strafing. When all seemed clear we set off again for the town.

It was late morning when we got there and there was chaos; men were trying to get out to ships off shore, most of which were naval ships, which was the only reassuring sight about the place. We made our way towards the harbour wall which stretched out to sea but did not get too close because it was periodically being shelled. When this happened the warships off shore opened up and this seemed to have the desired effect of quietening things down for a while.

We started to make enquiries of others around us and we discovered there was some food available in one of the sea-front shops and we got 2 tins of bully beef which was most welcome.

We also learned that we had to get ourselves organised into groups of 30 men with an officer in charge, and then register at the harbour wall. It did not take us long to find a stray officer and I think he was just as pleased to be in an organised group. Our officer and a sergeant-major went off and registered our group; we were given a number, we were about 140 something.

We were told that embarking would begin after dark off the harbour wall, about 9 pm. It was still early afternoon so we had quite a bit of time to hang around.

At last darkness slowly crept in. Group numbers started to be called, and morale got higher. It was after midnight when our turn came and we got in the queue at the sea wall.

The problem was that 2 big gaps had been blown in the wall and these had only been bridged by 2 planks of wood over each gap. We were given specific instructions by the Military Police to walk up and over the planks very carefully, but once over to run like hell and get on any ship you liked. We needed no encouragement to do just that. (At least Arthur didn’t have to wade out to sea like these poor chaps).

Having got to the ships, they were high in the water, and one had to climb up scramble nets. But once near the top 2 hands grabbed you and you were on board and immediately sent to one of the lower decks. One just found space to sit; the ship got more and more full and one thing was sure; if anything happened to that ship not many below decks would get out. But at the same time it seemed a better bet than being on Dunkirk sands.

It seemed ages before we set sail. Then someone brought round a mug of tea; only a swallow was allowed and then you had to pass it on, but it was the best I had tasted for many a long day. When the white cliffs of Dover were in sight more of us were allowed on deck. It was the most welcome sight I can remember.

There were a lot of trains in the station, and we were told to get on any one of them. When we stopped at any stations there were local ladies with cups of hot tea and home made buns and they even took hastily written messages to send to our homes.”

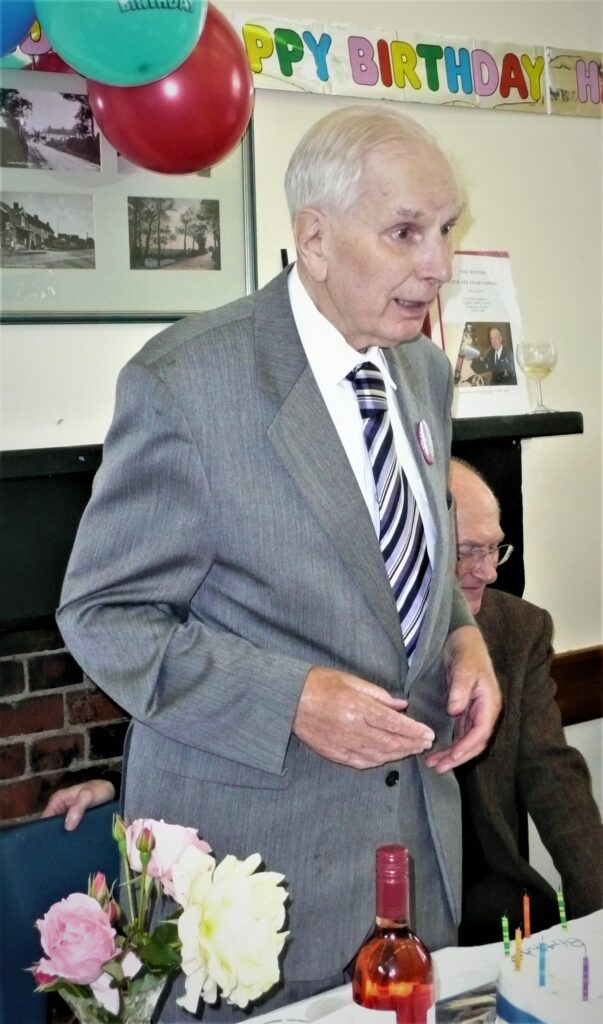

Arthur Lambert was my uncle. He survived the war, seeing much of the European theatre in the process. He was in the artillery with the 8th army in Egypt then fought in Italy, then landed with the D day landings on 7 June. He was in Belgium and Holland, made his way through Germany and he was in Schleswig Holstein for VE day when he celebrated with a huge bonfire and burned a swastika flag at its summit. He ended up in Berlin with the first British occupation troops, which at the time was occupied by the Russians. He was most impressed with the Russian woman soldiers positioned at each road junction. They were dressed very smartly with a navy forage cap, khaki tunic and navy skirt with jack boots and with a rifle slug across the back. They would carry to little triangular flags, one in each hand, and direct each vehicle as it approached where it was required to go and then saluted every vehicle as it passed by.

He was still in Berlin for VJ day when he was billeted in the Olympic stadium. He was also one of the first soldiers to receive penicillin. It was sprayed out of a kind of scent bottle and it sorted out his impetigo. Fortunately he was never injured and lived happily to the age of 90 years.

He was a lovely man who I remember very fondly.